How Advances in HVAC Are Affecting Indoor Comfort and Occupant Health

It’s said that if you do what you’ve always done, you’ll get what you’ve always got. While that’s generally true, it can lead to dangerous consequences when it comes to residential heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

That’s because new homes and the rules governing their construction and performance aren’t what they used to be. Each successive version of the International Energy Conservation Code, not to mention nuances at state and municipal levels and the proliferation of green building certification programs, sets a new baseline for residential energy use, which, in turn, affects issues of indoor comfort and occupant health.

While improvements in HVAC system and equipment design and performance usually anticipate or closely follow incremental code changes, there are also some truly innovative (and commercially available and code-approved) solutions that enable builders to go beyond the status quo to deliver more reliable indoor comfort and health to homeowners.

Those innovations, from ductless multi-zoned and next-gen geothermal heating and cooling systems to industrial-grade air filtration, whole-house fresh-air ventilation, and air-tight duct sealing, help builders keep pace with what codes intend, new standards require, and what consumers increasingly demand.

The Mini-Split Option

About 85% of new homes rely on forced-air electric or natural gas furnaces, air-conditioning units, and heat pumps to deliver conditioned air to the entire home. But as building science experts and energy code writers look more closely at that system, it’s clear that new and more efficient and reliable solutions are needed.

A ductless multi-split (or multi-zoned) heating and cooling system connects one or more small indoor air-delivery units to a single slim-profile outdoor condenser, allowing homeowners to control the temperature in a room or small area (or “zone”) of their home independent of other rooms or areas. “Each indoor unit can be set to different temperature set points to meet a homeowner’s specific needs,” says Andrew Bugg, ductless development manager at Ingersoll Rand.

That kind of flexibility not only helps deliver better comfort (think a warm kitchen or bathroom in the morning or an occasional guest room left unconditioned until needed), but also requires less heating and cooling energy than a typical central forced-air system serving the whole house.

Addison Homes, a high-performance builder in Greenville, S.C., completed its first two homes with ductless mini-split systems in 2018 and started two more last year. “Ductless VRF [variable refrigerant flow] systems allow us to avoid having ductwork outside the conditioned space of the house,” says company founder and president Todd Usher, which eliminates wasted energy and money through leaky ducts (see Sealing Duct Runs, on page 106).

Carl Seville, a former builder and now a partner at SK Collaborative, a better-building consultancy in Decatur, Ga., relies on just one outdoor condenser for a ductless mini-split system serving the two-story, 2,646-square-foot home he recently built for himself. The setup achieves a 30 SEER (Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio, as defined by the Air Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute in its 2008 standard AHRI 210/240) rating for space-cooling efficiency compared with traditional forced-air systems with SEERs in the high teens or maybe low 20s.

For Usher and Seville, among others on the mini-split bandwagon, the system only really delivers when the house is built to require less energy for indoor comfort. “The lower the energy load of the house, the more ductless make sense,” says Gord Cooke, a partner at Construction Instruction, a building science consulting firm in Denver.

Still, just 4% of new homes built in 2018 used a ductless system for heating and/or cooling, according to research, testing, and consulting firm Home Innovation Research Labs. One reason is cost: The premium of a ductless system could be 14% to perhaps 50% compared with a 15-SEER central forced-air system. “Until production builders get some other incentive to do something different, they’ll continue to acquiesce to the lowest common denominator,” Usher says.

Next-Gen Geothermal

Conceptually, geothermal heating and cooling is an efficient solution for delivering reliable indoor comfort. After all, just 10 feet below the frost line the temperature regulates to a consistent 45° F to 70° F, depending on the area, which serves as a heat source in the winter and a heat sink in the summer.

The hitch is the cost to tap that resource with a loop of tubes to enable it—historically about $40,000 per house—relegating geothermal to a scant 2% share among new homes built in 2018, according to Home Innovation research.

New York City-based Dandelion aims to change that game. Conceived in 2017 at X, Alphabet’s innovation lab (that is, Google’s skunkworks), Dandelion offers a geothermal solution that cuts conventional costs in half. Some of those savings come from state and federal personal income tax credits (the latter providing 26% off the price of the system in 2020 and 22% in 2021), among other incentive programs through local utilities or municipalities.

But the real secret is in the company’s sonic drilling system, which reduces friction on the drill bit and shaft, allowing it to cut through various earthen materials more quickly and precisely. Dandelion’s proprietary version also is smaller and more mobile than conventional well drills, a setup that enables it to be a one-day job and makes the drilling process—the cost-prohibitive aspect of geothermal—more affordable at a residential scale.

“The industry has been using [water] well drills to install the loops, which are messy, expensive, and not designed for geothermal,” says Ilyas Frenkel, head of marketing at Dandelion. “We can do installs at scale.”

Other cost-savers include offering just a handful of different-size models of water-to-air heat pumps, meaning Dandelion buys and stores equipment in bulk to reduce those costs. Its warehouse and in-house workforce are capable of up to 30 installs per month. “We’re not a mom-and-pop boutique shop,” he says.

Dandelion’s current market range is upstate New York, where the company has done hundreds of installs (20% of which are new construction, Frankel says, usually in collaboration with a builder’s HVAC contractor) and has plans to expand across the northern U.S. as its solution gains traction. “We’re where solar was 10 years ago,” Frankel says. “And in 10 years, we’ll be where solar is now.”

At least one national production builder shares that vision. Lennar Ventures, the investment subsidiary of the largest home builder in the U.S., contributed to an investment round that netted Dandelion $16 million last year. “Geothermal has always been on our radar,” says managing general partner Eric Feder, who is intrigued by a longer-range vision of geothermal at a community scale. “We’re active participants in helping shape their thinking and improve their processes.”

High-Tech Air Filtration

Air filters are standard components of forced-air systems, and their performance—driven by more stringent standards to achieve cleaner indoor air—has improved in the last decade or so.

But the latest and greatest central air filters designed to capture ever-smaller (and the most harmful) particulates tend to restrict airflow of the central system’s air handling unit (AHU), reducing the effectiveness and efficiency of the entire HVAC setup. “The reality is that air filters are hampered by the internal limitations of a traditional heating and cooling system,” says CR Herro, VP of innovation at Meritage Homes, in Scottsdale, Ariz. “There are limits on what we can do to reduce particulate matter with fresh-air exchange systems.”

Always on the lookout for innovations that solve problems and perform better, Herro recently came across the Super V by HealthWay (watch an installation video here), a filtering system decoupled from the AHU that uses DFS (disinfecting filtration system) technology to essentially “clump” or consolidate the smallest particles together before they reach the filter, making it easier for the unit’s media to capture them.

Impressed by HealthWay’s demonstration and already hip to DFS technology, Herro installed the unit in his own Meritage home, and within minutes saw the particulate count drop from 500 to 0 … and stay there. “I’d never seen anything do that before,” he says.

He’s now working with his design team, HVAC trade and supply chain partners, and HealthWay to standardize the Super V’s installation to achieve a total cost that doesn’t hamper sales or profitability. “The intent is that it becomes standard in our homes,” he says.

Patrick Hamann, president of UrbanLux Builders, in San Antonio, learned of Super V from his HVAC contractor and was blown away by HealthWay’s demo. “I thought ... If this can be affordable, it’s definitely a difference-maker,” he says.

Like Herro, Hamann started with a portable unit in his own home and experienced first-hand how it reduced the effects of “cedar fever,” a common winter allergy, within his family. He then installed the system in a few new homes, with all-positive feedback. “The houses smell clean and it’s amazing how quickly it gets rid of that ‘new-home’ smell—even when you’re careful about using non-VOC finishes,” he says.

That experience convinced the self-professed skeptic of air filtration to install Super V systems in a 37-unit townhouse project selling in the $270,000s, a $600 upgrade over a standard 4-inch AHU filter. “It’s now standard in every house I build,” Hamann says.

Balanced Ventilation for Homes

Fresh-air ventilation presents another challenge for high-performance, low-load homes. Most builders understand the “build tight, ventilate right” axiom but aren’t sure how best to deliver it. “Few builders truly understand ventilation requirements because the building code isn’t clear,” says Tim Kampert, a building performance specialist with IBACOS, a construction quality assurance firm in Pittsburgh. “As a result, ventilation equipment is all over the map.”

Often, it’s simply relegated to localized, exhaust-only units, namely a range hood in the kitchen and ceiling-mounted fans in baths and laundry rooms. Just 27% of new homes in 2018 had some sort of whole-house ventilation scheme, according to Home Innovation research. But as homes get tighter and tighter to reduce their heating and cooling energy use, “a comprehensive ventilation solution becomes more critical,” says Paul Raymer, a senior technical specialist at global consulting and technology services company ICF International, in Falmouth, Mass., and a contractor to the U.S. EPA’s Indoor airPLUS program. “As homes become more sophisticated, ventilation is not as easy as it used to be.”

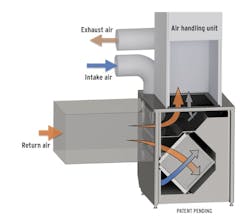

Heat- and energy-recovery ventilators (HRVs and ERVs, respectively) are conceptually the most effective options for controlled, whole-house, fresh-air ventilation, but they’re also expensive—one reason why just 12% of new homes have them.

The relatively space-efficient units are usually coupled with the AHU and ductwork of a central forced-air system, and therein lies the problem: “A typical AHU is far more powerful than the fans of an H/ERV,” says Srikanth Puttagunta, principal mechanical engineer with New York research and consulting firm Steven Winter Associates (SWA). That dynamic impedes the flow of fresh air into the home and/or exhaust air out, he says, as well as causing unintended pressurization differences that almost ensure an H/ERV will fail to work as advertised. “Builders believe an H/ERV ensures good indoor air quality, but that’s seldom the case,” he says. “I’m not bashing HRVs and ERVs, but there’s always room for improvement.”

Variable-speed AHUs help, but the proper balance between the AHU and the HRV/ERV can only be commissioned at one of those speeds, says Puttagunta, so the problem still exists.” HRVs and ERVs work best when installed with a dedicated distribution system.” In other words, their own ducting.

That’s a highly unlikely and cost-prohibitive scenario for most builders, so SWA is collaborating with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) and an HVAC equipment manufacturer to develop an H/ERV that delivers its intended performance in a shared-duct scenario.

The SWA unit, for which the firm is eyeing a 2020 launch, will connect directly to the return side of an AHU to pull stale air from the air handler’s return ductwork, thus reducing the number of duct connections by half, which also will help render proper installation. With that, SWA’s unit uses constant flow fans, which the firm says will better ensure balanced ventilation under constantly varying conditions, including AHU fan speeds, outdoor winds, and indoor pressure changes.

“If you’re going to pay the cost premium for an E/HRV, you should get the full benefit of it,” Puttagunta says.

Sealing Duct Runs

A remarkable 10% to 30% of conditioned air leaks out of forced-air HVAC system ductwork through small fissures, poor connections between sections, and actual holes in the run. Considering that more than 90% of new homes use a forced-air scheme for heating and cooling, the loss of energy and money is especially bad in newer, lower-load homes built for better performance.

For sure, builders and their HVAC contractors need to pay attention to basic best practices for tight duct installation, such as using mastic paste, zip ties, and flashing tape at connections, and placing ductwork in conditioned spaces to mitigate differences in pressure, temperature, and humidity that can promote leakage.

But once that’s done, ducts can still leak. Enter Aeroseal, a water-based, nontoxic aerosol sprayed into pressurized ductwork that finds and seals fissures up to 5/8-inch wide. “It’s like Fix-a-Flat for ducts,” says Stephen Rardon with Rardon Home Performance, in Garnet, N.C., one of more than 300 Aeroseal installers across 40 states. “Even if you manually seal all visible cracks, there’s always something you won’t see, but this stuff finds it,” he says.

Funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and developed at LBNL in the mid-1990s, the technique has proven to seal 70% to 90% of duct leaks and is guaranteed to last 10 years. Aeroseal, in Miamisburg, Ohio, commercialized the technology nearly 20 years ago and claims 100,000 residential installations to date.

But, like most innovations, Aeroseal suffers from a cost that is four to six times that of manual duct-sealing practices, says Rardon, a premium driven by licensing fees for each job, the sealant material, and the time spent preparing and performing the seal.

The upcharge easily dissuades most home builders. “Customers for this product tend to be builders who need to meet a performance standard, like Energy Star,” says Rardon, who has yet to sell the technique to a builder, but has convinced a few homeowners. “The difference between manual sealing and AeroSeal is night and day because manual sealing practices are rarely followed.”

Access a PDF of this article in Pro Builder's January 2020 digital edition

About the Author

Rich Binsacca, Head of Content

Rich Binsacca is Head of Content of Pro Builder and Custom Builder media brands. He has reported and written about all aspects of the housing industry since 1987 and most recently was editor-in-chief of Pro Builder Media. [email protected]