Shipping Containers, Steel, Wood: A California Firm Goes 'All In' on Modular

An irony of affordable housing? It costs so much to build. In addition to the same pressures facing market-rate housing (such as rising land and construction costs), affordable housing faces increased scrutiny, such as local government design requirements—further driving up costs.

Consider California, where labor and land costs notoriously run high. From 2000 to 2019, the per-unit cost of building an affordable housing project rose over 80%—from $265,000 to $480,000. (Compare that to the national average cost of constructing a new home: around $297,000 in 2019 and about $333,000 this year.)

Today, the per-unit cost of affordable housing in Southern California hovers around $600,000, says Michael Bohn, senior principal, Studio One Eleven, an architecture firm based in Long Beach and Los Angeles, Calif. Prevailing wage and complex financing play a big part in that cost, he adds.

“We scratch our heads because we can do luxury housing for cheaper than that,” says Bohn, whose firm designs projects ranging from commercial developments to luxury, middle, affordable, and homeless housing.

But there’s another, cheaper way to build affordable housing, Bohn says, and that’s modular construction.

SHIPPING CONTAINERS FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING

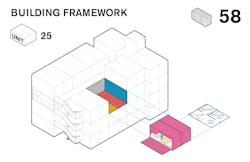

After designing commercial projects made of shipping containers, such as an outdoor eatery, Bohn’s firm decided to use containers for an affordable housing project. For Watts Works, completed this year, Studio One Eleven used 58 shipping containers to create 24 studio apartments for homeless individuals.

The 8’x20’ containers, which cost about $3,500 each, had been used to ship goods from Asia to the Port of Long Beach. The containers were sent to a fabricator, which cut them up, installed the interiors, and then delivered them as finished modules back to Southern California, where they were installed by crane. Onsite, the modules were joined together, the systems (such as water and sewer) were connected, and the exteriors were finished.

With Watts Works, the firm realized significant savings: The project cost $400,000 per unit, about 20% less than conventionally built affordable units.

Those savings were achieved in a few ways, Bohn says. First, factory construction means more efficiency and less waste. Factory construction has about 10% to 15% less material waste, according to Bohn.

Second, at the same time that the factory built the modular units, the contractor completed the onsite work involving the foundations and utilities. “That alone saved about 3.5 to 4 months in construction,” Bohn says.

And third, he says: “We discovered the state of California is a lean, well-oiled machine” when it comes to reviewing and approving modular projects. The firm gained approval for Watts Works in about 15 business days—shaving months off traditional review time.

Containers are easily stackable during transport and easily movable by crane during installation, Bohn says. They also work well for studio housing, where two containers can be put together to form one studio. Containers are also less prone to cost escalation than lumber. “And there is a sustainability component,” Bohn says. Watts Works’ recycled containers equaled about 108 tons of material.

But containers come with challenges, too, he says. Their dimensions don’t easily accommodate conventional unit sizes, such as two- or three-bedroom units. As a result, using containers for larger units would involve a lot of cutting and removing of container material, which would take more time and money.

After Watts Works, Studio One Eleven forayed into three modular projects made of steel: Vanowen Apartments and Oatsie’s Place, fabricated by indieDwell, and McDaniel House, fabricated by CRATE Modular. With 46 to 48 units each, Vanowen will house homeless individuals and transition-aged youth, Oatsie’s Place will provide housing to women experiencing homelessness and survivors of domestic violence, and McDaniel House will offer affordable housing for seniors. All three are scheduled for completion next year.

MODULAR HOMES WITH WOOD AND STEEL

More recently, Studio has embarked on a modular project made of wood, the Armory Arts Collective. The project will restore an armory and convert part of it into 58 affordable housing units for teachers and artists.

Compared to containers, steel and wood can more easily create bigger units, Bohn says. Instead of having to use two shipping containers to form one studio, steel or wood can be used to form a single studio module. That results in larger modules but also more efficiency, since the bigger modules involve less onsite assembly work.

Wood presents another advantage, Bohn has found: Trades and subcontractors are a lot more comfortable with wood than they are with steel or certainly shipping containers. “There seems to be a psychological comfort in the industry with wood.”

But wood poses its own challenges. In conventional construction, the flooring for one unit doubles as the ceiling for the unit below. With modular, there’s redundancy between the roofs and floors. As a result, “you might lose a whole floor” on a wood modular development, Bohn says.

Each material has its pluses and minuses. “This is where understanding different modules is important,” he says. Not every modular material works for every modular project.

And modular doesn’t work for every construction project, Bohn says. Two technicalities could preclude the use of modular from the get-go, he finds. For one thing: power lines, since utility companies won’t allow craning modules over power lines. And for another: not enough room onsite or offsite to place the modules once they’re delivered from the factory.

Challenges aside, “we are all in on modular,” Bohn says. “It’s not the solution for every development; conventional construction still has its place. And modular is still in its pioneering stages. But we see positive results that will only get better over time as the industry gets more familiar with it.”