How to Build Healthy Homes That Protect Homebuyers From Radon

A silent poison, a fatal gas, an invisible killer. It goes by many names, but to the building industry and a growing portion of the population, it’s known more commonly as radon. While its nicknames may seem extreme, this odorless, invisible, radioactive gas can lead to lung cancer and other health issues for building occupants who are exposed to it over time. In fact, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), radon is responsible for approximately 21,000 lung cancer deaths each year, second only to smoking.

Where Does Radon Come From?

Radon is produced naturally from uranium located in rock and soil. Without getting too technical, as part of its decay process, uranium breaks down into radium, which then converts into radon gas that travels up through the rock and soil and into the air … unless that ground is covered by a house.

In those cases, the gas usually infiltrates the indoor environment through cracks and gaps in basements, foundation walls, crawlspaces, and concrete slabs. Radon releases even more decay products into the air as it continues to break down, except now it’s trapped indoors. These radioactive decay products are what cause health issues when inhaled into the lungs in large amounts over time.

RELATED

- Radon Mitigation Products for a Healthier Home

- For Better Indoor Air Quality: Build Tight and Ventilate Right

- When It Comes to Crawlspace Ventilation: Do You Vent or Not?

- Breathe Easier—Healthy Homes Go Mainstream

What Is Radon, and Why Should You Care About It in Homes?

The common response I hear when talking about radon and radon mitigation requirements on construction jobsites goes something like this: “I don’t know why people make such a big deal about radon now. It was never an issue when I was young!”

In fact, the effects of radon were documented as early as the 1600s in European coal mines. Unfortunately, the deaths observed at the time weren’t able to be properly classified because radon wasn’t officially discovered until 1900 and has only been known as “radon” since 1923.

And it wasn’t until the mid-1980s that the first radon guidelines went into effect, following a 1984 study that found high levels of radon in a large number of homes in Eastern Pennsylvania and examined its impact on human health. The case created enough concern about radon’s health risks that the EPA introduced recommendations on safe levels of radon exposure.

Pennsylvania Incident Leads to Radon Awareness

In 1984, what became known as the "Watras incident" involving American construction engineer Stanley Watras—an employee at a U.S. nuclear power plant in Pottstown, Pa.—led to the discovery of the highest radon reading ever in Pennsylvania and ultimately urged the EPA to get involved in monitoring radon levels in residential homes. Watras triggered radiation monitors while leaving work over several days—even though the plant hadn't been filled with nuclear fuel yet. This pointed to a source of contamination outside the power plant, which turned out to be in the basement of his home, where radiation levels were measured to be 700 times higher than the maximum level considered safe.

Even so, it wasn’t until as recently as 2009 that radon was identified as the second leading cause of lung cancer by the World Health Organization.

Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to reduce radon levels to zero, and varying levels of it are found across the United States. To help define and locate high-risk areas, the EPA has created a radon zone map (see below) showing the potential for radon at the county level across the country. “Zone 1” (in red on the map) has the highest potential levels of radon, “Zone 2” (orange) has moderate levels, and “Zone 3” has the lowest likelihood of radon concentrations.

What Can Be Done to Mitigate Radon?

But even in lower-risk areas, the EPA recommends actions to mitigate radon levels when they are above a concentration of 4 pCi/L (picocuries per liter). Some municipalities have even gone a step further by requiring home builders to provide mitigation strategies at lower levels of exposure.

The good news is that over the years, we have developed effective methods of mitigation to keep radon at safe levels for home occupants.

The location of the house and its foundation type ultimately determine the proper method, but most radon-savvy new-home builders use “soil suction” or “soil depressurization,” which is the mitigation method we’ll focus on here.

The soil suction technique involves stopping any radon from entering the house by containing it below the foundation, collecting it into a tube or pipe system, and venting it up and out the side or top of the house, where it dissipates to essentially harmless levels in the open air.

RELATED

- Indoor Air Quality Road Map: A Smart Range Hood

- Webinar: Indoor Air Quality for the Healthy/Clean Home

- Gas Sensor Monitors Health in Homes

- Biggest Causes of (and Solutions for) Home Air Contamination

How to Install a Radon Mitigation System

While installing this system may seem simple, there are a few critical details to ensure it contains and vents as much radon as possible.

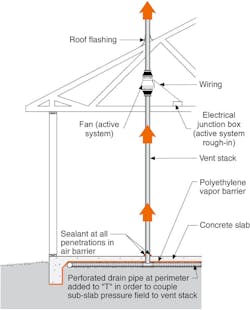

First and foremost, the system must contain the radon below the house. Regardless of foundation type, the process starts by installing perforated pipe in the substrate, typically encircling the inside of the foundation or under the perimeter of the slab. Think of it as creating a highway that radon gas will take to travel out of the home. (Bonus: In many cases, this piping can double as a perimeter drainage system when paired with a sump pump or other methods.)

Then, the pipe is buried with no less than 4 inches of gravel (preferably ½-inch diameter aggregate or larger) to create a collection area for the radon. The gravel creates a path of least resistance for the gas to move easily underneath the substrate and toward the piping.

The last step is to install a minimum 6-mil polyethylene vapor retarder on top of the gravel, ensuring any seams between sheets are properly taped and sealed, along with any penetrations. If you’re building on a crawlspace, then you may need to seal along the edges as well, to contain all gases under the plastic.

Once you have the substrate portion done, the next step is to connect a “tee” fitting to the underground pipe to penetrate the foundation and draw gas vertically. As a best practice, seal all cracks, gaps, or holes in the slab or foundation floor, including the gap where the slab meets the walls in full basement or crawlspace situations.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in 15 U.S. homes has high radon levels.

Then connect a solid (unperforated) PVC pipe to the tee fitting, ideally outside of conditioned space or in a sealed area, and run it vertically up and out of the house. Similar to a fireplace, you are essentially creating a chimney whereby air pressure differences within the pipe will carry radon from the lowest point to the highest.

As mentioned earlier, some builders choose to run the vent pipe through the roof, while others direct the piping out of a side wall of the house. Be aware that each method has specific guidelines to ensure its effectiveness.

For example, when expelling radon through the roof, most jurisdictions have requirements regarding how high the pipe must terminate above the roof. When expelling radon out of the side of a house, be aware of clearance requirements from windows, doors, and other openings that may allow the vented gas to reenter the house.

Another aspect to consider, often dictated by local jurisdictions, is whether a builder is allowed to install a “passive” system, such as soil suction, or an “active” system that requires some sort of mechanical ventilation, such as a fan to pull the radon from the lower levels up and out of the house. Even with a passive system, I often recommend including a powered receptacle in the attic in the event the homeowners want to make the system “active” at a later date.

Make Home Occupant Health a Priority

Radon is not your typical “out-of-sight, out-of-mind” gas. Whether for your personal health or that of your loved ones or clients, being aware of the risks associated with radon can help spare people from serious health implications in the future.

If you’re a builder, I encourage you to look into radon levels in the areas where you build, if you haven’t already. If radon levels are high in those places, consider mitigation as part of your standard details and make the health of your occupants a priority—an increasingly important selling point among today’s homebuyers and a distinct advantage over existing homes, in which radon mitigation is far more difficult and expensive to do.

If you’d like to learn more, there are many great resources available from the EPA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including how to test houses for radon and how to reduce radon levels that are higher than recommended.

RESOURCES

- EPA Radon Resources for Builders and Contractors

- EPA: Radon-Resistant Construction Basics and Techniques

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Radon Resources

About the Author

Andrew Shipp

Andrew Shipp drives quality and innovation in homebuilding as a building performance coach and client relations manager at IBACOS.