I can recall at least 10 times in our country’s history when authors and pundits, recounting the aftermath of a major event, concluded with some version of “Our world will never be the same.” The implication is not merely awareness of the change, but a need for us to think and act differently.

The incident anyone over 30 will cite first is now known simply as “9/11,” when terrorists simultaneously crashed hijacked airliners into New York City’s World Trade Center towers, the Pentagon, and a remote field near near Shanksville, Pa. We were all glued to the news for days and each talking head seemed to end his or her time on air with some version of “Our world will never be the same.”

Some things are different in the aftermath of 9/11, airport security being the most obvious. Today, however, with Transportation Security Administration (TSA) PreCheck registration and Clear (a private service that uses your fingerprints and an iris image scan to confirm your identity), I pass through security with hardly a thought.

Considering the incredible depth of the tragedy, 9/11 caused relatively few behavioral changes for individuals. And for those under 30 years old, who have grown up with TSA, their world remains the same.

Coronavirus Presents a Whole New Crisis

As I write this column, the novel coronavirus pandemic has exploded globally and now especially in the U.S. On the day of my final edit, deaths attributed to the virus are averaging over one per minute in this country, and predictions are the situation will grow worse. Most every state has instituted stay-at-home orders and social distancing, closing schools and restaurants and prohibiting public gatherings, as well as restricting work to “essential” activities, primarily those for public health or safety. Members of Congress twist themselves in knots developing the most effective stimulus packages, and economists debate the impact. President Trump’s former proclamation of “Open the country and back to work by Easter!” is now described as either aspirational or delusional, depending, I suppose, on your personal politics.

The latest findings show minimum mortality of 10 times the traditional flu strains (1% compared with 0.1%). COVID-19 also is far more communicable than a typical flu virus, survives on surfaces much longer, and can be passed on by asymptomatic people. That doesn’t bode well for quick resolution. By the time you read this article, things should be better, but in no way will we be fully out of the woods.

Most predictions for the number of U.S. deaths are now between 100,000 and 200,000, but some models predict a tenfold increase if we don’t follow the social distancing and stay-home/stay-safe rules. My fervent hope is you are saying right now, “Chill out, Scott, our efforts worked. We held the death count down. We flattened the curve. Hospitals received their personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators. Testing is universal, with new cases at next to nothing. Schedule your trips and meetings again. Back to work!”

When the coronavirus pandemic is over, will our behaviors change? What will be the lasting impact?

That would be great. But when this is all over, will our behaviors change? Will handshakes disappear? Will hand sanitizer be your constant companion, a mask always ready in your pocket? Will phone apps replace credit cards and keypads to purchase almost everything? Will you avoid using the handrail, pole, or strap on every train, bus, or airport shuttle? Will we be compelled to wipe down every surface inside a rental car? And wiping down tray-top tables and armrests on planes will probably be de rigueur for the next six months, maybe a year. How about in three years? Ten years?

Events That Changed the World—or Did They?

I hope it doesn’t come to that, but this got me thinking back to those events in my life where the world was said to have changed forever. Did those events change both thinking and behaviors? Think about yours, make a list, and see what you find. Here are some of mine.

1957: Sputnik

The Commies are coming! My 1st grade teacher Mrs. Meyers lectured us each day on how the Germans nearly took us in World War I and World War II. And now, beware the Russians.

The entire country was consumed with the threat of the “Red Menace.” Did our world change? Bizarre behavior abounded, highlighted by the McCarthy hearings in Congress and blackballing anyone suspected of having communist ties or sympathies.

The space race was launched, but we caught up to the Reds with the Mercury missions of the early 1960s, and the Gemini launches in the mid-’60s clearly pulled us ahead. After the Apollo series in the late ’60s, namely the moon landing in 1969, we never looked back. Strangely enough, beating the communists in space seemed to reduce, in our minds, the political threat at home. Go figure.

1962: Cuban Missile Crisis

Few people today recall how close we were to nuclear conflagration with the Soviet Union when we discovered their nukes in Cuba and blockaded the harbors. Yet it fed our national psyche, where the threat of a nuclear war lurked always in the back of our minds.

The crisis made the Cold War threats up front and personal, and the fear of Russian missiles arcing up and over the horizon was the subject of news reports, documentaries, and countless made-for-TV movies all the way into the ’80s. That was a big change in our thinking, and although it had a huge influence on government spending, it rarely affected our day-to-day actions. Beyond the weekly “duck and cover!” school drills, which scared the kids for sure, little else changed in terms of behavior.

1968: The year of mayhem

With the Vietnam war ever present on our TV screens and in our minds, the daily death toll staggered the nation. We burned through resources fighting a war no one could quite explain. Nerves were frayed, our country split wide open. Against that backdrop, Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated, while the violent beat-downs of protesters by police at anti-war and civil rights demonstrations, as well as the calamitous Chicago Democratic Convention, were broadcast nightly.

That May I met Bobby Kennedy personally, as our group of local high school newspaper editors interviewed him while he sat on his plane, having his hair trimmed. One month later, RFK was dead. The loss of John Kennedy five years prior was no longer a horrible aberration, a once-in-a lifetime thing. It could happen to any of our leaders. For me personally, what innocence I still had was gone. I began to think differently and was suspended three times for “inappropriate” high school editorials I wrote calling it like I saw it! That was behavior change, but still I qualified as an aberrant data point among the general population.

1970: Violence at Kent State University

A few weeks prior to my high school graduation, and less than 200 miles from my home, the four student deaths at the hands of the Ohio National Guard told us no one was safe. Such violence could happen anywhere, even on the bucolic campus at a university in the Midwest. For my generation, this was the last straw in the fragile bastion of institutional trust; a feeling many of us carry to this day. But combine a war that resulted in more than 50,000 needless U.S. military deaths, with a spate of assassinations, and institution—from college administrations to police forces to the nation’s president—responding out of fear, and yes, our world had changed.

1973: Vietnam War departure

Some still won’t call it the defeat it was, but what we had believed impossible happened. America lost its first war in its then nearly 200-year history. Exactly what happened in the Vietnam War, and why, is still debated today. It’s true our military was underequipped, undertrained, and had its hands tied at every turn by both the Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon administrations.

But, all that aside, we ran from Southeast Asia with our tails between our legs. The panicked scenes of planes, helicopters, and thousands of boats evacuating the South Vietnamese while the Viet Cong rolled into Saigon played more like a horror movie than real news. While the subsequent humiliation didn’t change the behavior of individuals in this country, it exerts considerable subtle but very real influence on our politics and military to this day.

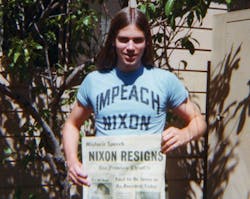

1974: Nixon’s resignation

When Marine One lifted off the White House lawn carrying Richard Nixon, it was a seminal moment those who watched will never forget. Our world changed that day with another barrier broken. A sitting U.S. president was forced out of office.

As much as most anyone under 30 at the time despised Nixon, it was still a profoundly sad thing to watch. Sometimes justice for a perpetrator, no matter how thoroughly earned, is anything but pretty.

For me, that was a significant. I expected a feeling of gratitude, maybe even joy, yet there was none of that. I was just sad for our country, for what we’d endured, and what it took to set things right. Behavior change? Not outwardly but inwardly, we became more suspect of our leaders than even before. Nixon’s subsequent pardon by President Ford didn’t do anything to repair the damage from that broken trust.

Early 1980s: Hyperinflation and the mortgage crisis

High inflation was a consistent problem through the 1960s and ’70s, but the low point was 1981 when 30-year mortgages reached a peak of 18.5%. Inflation in that era crept over 13%.

Unimaginable today, there was significant behavior change for the next 10 to 15 years as a result, especially for those of us with young, growing families. Each rate point drop meant a refinance, sometimes multiple times in a year. My wife and I were thrilled to finally refinance below 8%, believing that was the lowest it could ever go.

Today, a mortgage rate over 4% would kill the market. Inflation has surpassed 4% only once since 1990 and has remained under 3% since 2008. Hyperinflation is either unknown or just a dim memory for 90% of the population, but fear of it still affects decisions made by Congress and the Federal Reserve.

Our world will never be the same—let’s hope not.

1991: Fall of the Berlin Wall

This was a change of earth-shattering proportions. The Berlin Wall stood as an ever-present reminder of the Cold War, a fixture on nightly newscasts. The collapse of the Soviet Union had been in progress, but this was the culmination, the proof, that the ever-expanding communist regime had failed. Communism as an ideology was dealt a massive blow.

Personal behavior didn’t change much, but the world sure looked different. It was now possible to overthrow totalitarianism without bloodshed and restore a country to democracy.

1990s: The rise of terror at home

Terrorism was hardly invented in the 1990s, but it did reach new levels. With the exception of embassy and military barracks bombings in Lebanon, most prior attacks on Americans happened overseas. But the 1993 World Trade Center bombing followed by the Oklahoma City Federal Building blast in 1995 brought terror to a new level—on our own soil. Google search “significant terror events by year” and you’ll find just a smattering of events in the 1960s and ’70s. In the ’80s each year begins to show multiple events. In the ’90s you’ll find 20, 30, or more terrorist attacks for nearly every year—a monumental change. The reality, however, is that unless you had a personal connection to one of those events, little changed beyond a sense of heightened security. The trend continued into the new century most exemplified by the 9/11 attacks discussed earlier.

2020: COVID-19

Whether we are already largely in the clear as you read this or are still suffering restrictions for months to come, COVID-19 will surely run its course sometime in 2020. This is beyond anything I’ve seen in my lifetime, and again we wonder: Will our world ever be the same? Will the new behaviors I detailed earlier in this column become part of daily life, or in time will we cease to care? For the sake of our children, grandchildren, and generations to come, I adamantly hope not.

In retrospect, there was so much we could have done earlier and better in terms of stockpiling medical devices and PPE, proactively identifying potential threats, and taking pandemic emergency plans to a far higher level. The supply-chain debacle we witnessed while getting our health care system supplied will be analyzed and debated for years to come.

Perhaps COVID-19 seems more personal and threatening merely because it’s current and happening in the age of completely connected communication, with up-to-the-minute reports on all aspects. Most likely though, before this is over, all of us will personally know victims who died, taking our awareness to a new level.

The one thing we absolutely must do is learn from this pandemic and be far better prepared for the next one, both individually and as a country. And I’ll bet you, like me, are learning some other things, such as how much we take for granted in our everyday lives—our families, our friends, our jobs. We now have a heightened appreciation for the simple pleasures of going out to eat, attending a sporting event or concert, or maybe even the privilege of sitting in a traffic jam because that means everyone is working again.

The world, our country, our industry, and the vast majority of us will recover from this pandemic, but it won’t be the last one we confront. For reference, the bubonic plague (aka Black Death) of the mid-1300s killed approximately 50 million people in Europe, which was about 60% of the population, making our current pandemic seem trivial. And for the next four centuries, the plague continued to strike Europe, the Middle East, and beyond, every 10 to 20 years.

The Plague, an allegorical work by Nobel Prize-winning author Albert Camus, is about a European city decimated by an overwhelming epidemic, and how people cope and respond. Camus’ novel is gut-wrenching and is not an easy read. But the ending, which varies a bit by translation and I’ve simplified here for clarity, makes a profound statement we’d all do well to remember: that the plague will come again “for the bane and the enlightenment of men.”

How much bane and how much enlightenment is completely up to us.

About the Author

Scott Sedam

Scott Sedam is president of TrueNorth Development, a consulting and training firm that works with builders to improve products, process, and profits. A senior contributing editor to Pro Builder, Scott writes about all aspects of the home building business and won the 2015 Jesse H. Neal Award, business journalism's most prestigious prize, for his commentary in Pro Builder. Scott invites you to join TrueNorth's Lean Building Group on LinkedIn and welcomes your feedback at [email protected] or 248.446.1275.